Particles

June 15, 2022

Github repo for this project is here.

Goal and Motivation

The motivation behind this project was wanting to practice some more Rust and maybe see some of the flourishing ecosystem that is starting to grow around the language, but without an interesting context I find I can quickly lose interest in what I start. On top of this it is common for small projects to turn out to be not so small at all and fading away as the scope creep takes over. So for this project I wanted to create a MVP of a game I used to play on the primary school computers.

It's name has slipped my mind, I might not have developed my sense of conciousness at this point, but the premise was simple; place particles of sand, water, and all manner of elements in a 2D pixel simulator and see how they interact. Young me was fascinated, in no small part due to the ability to create sizeable explosions.

So the MVP for this project is simple:

- Render particles to the screen

- Place particles

- Change brush size

- Some sort of basic simulation - gravity

It's not going to be close to the game I used to play but the goal of this project isn't to create an award winning game, it's to experience an interesting part of the Rust ecosystem.

Bevy the Tank Engine

Bevy is described as "A refreshingly simple data-driven game engine built in Rust". The key part here is 'data-driven'. Traditionally a lot of games are built more OOP style but a data driven approach can come with a lot of benefits.

Data Oriented Design

Wikipedia, ever so wise, has the following to say: "data-oriented design is a program optimization approach motivated by efficient usage of the CPU cache, used in video game development".

Efficient usage of the CPU cache then must be the secret to this illusive performance increase but how exactly does that come about?

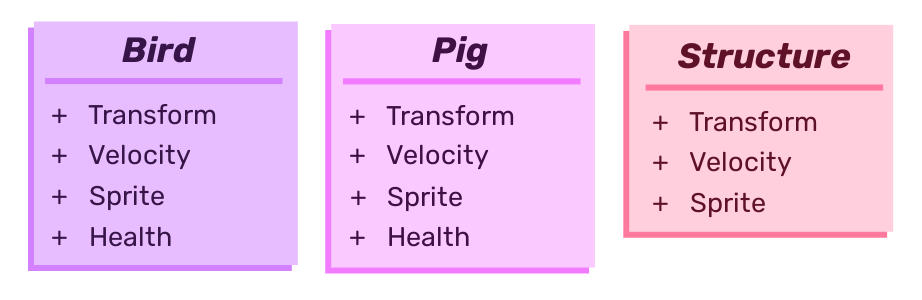

Firstly consider a simple game with the premise of an emotionally indifferent bird projecting itself at pre-bacon filled structures.

In an OOP approach to modelling this game we might have the following system, in which distinct classes are used to define the bird, the structure pieces, and the cheeky oinkers:

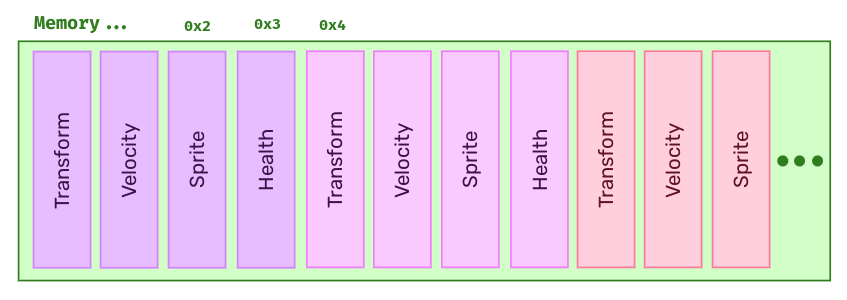

Now consider how this game works. A fundamental part of this is gravity, all of the elements in this model are effected by it, every game loop we will enact the force of gravity to every little piece. Unfortunately for performance the transforms (positions) of all the little buggers have scampered off in every which direction all over the memory. Now the engine has to go and find every last one of them to check the values and change them.

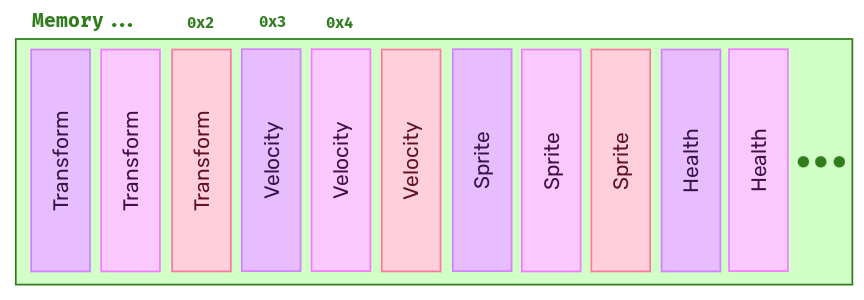

Wouldn't it be much faster if we could keep all the values we are likely to be interacting with all at once all together? Why yes it would, enter the data driven approach.

In this we would want to store the transforms of all the pieces in our model in contiguous memory. Then when it comes time to do our gravity iterations, not only does the engine not have to wander around the memory landscape rounding up all the little values like a primary school class released in a field, but perhaps we may be able to move the whole bundle of data onto the CPU cache.

This data driven approach in games is facilitated by a design paradigm called an Entity Component System.

ECS

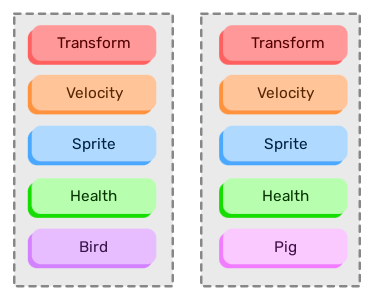

In OOP we would consider something like our bird as a strictly defined set of values, position, velocity, colour, speed, etc...

In ECS we transition to the far more easy to understand concept, familiar to the electron, of a flickering zone of potential values and components that if you squint just right do sort of look a little like a pigeon.

That might be a little unfair, once you wrap your head around the idea is does become a lot more ergonomic.

To understand it lets consider the three elements of the ECS:

- Entity - The identifying element of every 'entity' in the system, essentially just a primary key that can be used to identify a group of components

- Component - Defines an entity as having some desired aspect, as well as holding the data required for this aspect

- System - Iterates over groups of components that will be altered to achieve the desired behaviour

Let's create a simple version of our avian friend and our pig:

It is easy to see that these are built up of a lot of the same components (in fact only differentiated by the Pig or Bird component in this example), meaning they will have a lot of the same behaviours. By decoupling these behaviours from the entities it allows the engine to act on all components contiguously, greatly improving performance and promoting easier parallelisation.

Rendering

Right let's get to some actual code. Below is the bare minimum code to create an application and render it to the screen with Bevy. Plugins are just set of systems, the default plugins here include important things like setting up WGPU and creating a window.

use *;

My first goal is to render a set of walls near the edge of the screen, beyond which fun is strictly prohibited.

In Bevy to render to the screen requires a sprite. Rendering a single grey pixel to the screen is pretty simple.

// 👇 to interact with the world use commands

Before going any further I made some tweaks. For simplicity I wanted all my particles to be 1 unit wide, by default this would make them 1 pixel wide which is quite small. To make my life easier and have them all be 1 unit wide but be a little bigger I applied a scale to the camera in a setup system.

// taken from constants.rs

pub const SCALE: f32 = 5.;

To spawn the boundary walls I created two systems, the first spawn_boundaries which iterates over the required coordinates, and the second an agnostic reusable spawn_particle function which takes coordinates and places the particle.

The result is looking good:

Different Elements

In order to represent different elements I will need a component which contains the type of element. Bevy recognises components as structs with the Component derivation.

I defined a component Particle which contains its element as an enum variant.

// in componets/mod.rs

// in lib.rs

To expand spawn_particle and let it accept the element means making these changes (gravity component is also added for sand elements):

The Colours of Magic

Currently all the colours of spawned particles will be the same, not going to be the most appealing looking thing really. There are a few options for this. One common approach for a game like this is to use a sprite sheet but after about 30 minutes trying to understand how Bevy used sprite sheets I gave up and decided to do it in pure Rust.

One bit of functionality I want to incorporate is for particles to have slight colour variations to break up large areas of them, but I don't want this for all of the elements.

My solution involves some structs and some cool Rust pattern matching.

The solution involves a struct Sprites which will be relate an element to a SpriteType. SpriteType is an enum with two variants, the first is Single and contains a Bevy Color. The second is Range which contains a reference to a slice of an array of Color.

// populate the sprite sheet

pub const SPRITES: Sprites = Sprites ;

When spawn_particle now assigns a colour it will assign the colour based on the element. It matches the element to the sprite table for it and passes this to get_sprite_color. This function matches on the SpriteType, for single colours it returns the colours but for ranges it will choose one random colour from the array and return this instead.

// in lib.rs

// in sprites.rs

I'm quite happy with this system and it leads to much nicer looking sand.

Placing Particles

That last screenshot was technically cheating as I had placed those sand particles with my mouse but we'll take a look at how that works now.

Handling Input

The first problem here is handling the user input. Fortunately Bevy deals with a lot of that for us. By defining a system we can require the function receives both information about mouse buttons and information about the window which will contain the mouse coordinates.

Unfortunately it isn't all simple from here. The window will give coordinates relative to itself, from 0 to window width and 0 to window_height but this isn't going to correlate directly with the coordinates in the world. For a start the game has the origin at the centre. Then there's the pitfalls of resolution scaling and dpi.

Fortunately people much better at this than me already know solutions. For a fixed perspective 2D game like this Bevy has an example in the cheatbook on how to do this.

Once this is done it is just a matter of spawning a particle at the converted location (as long as it is within the allotted fun zone).

// Very simplified see source if interested

Different Brush Strokes for Different Brush Folks

One of the features of particle games like this is spawning more that one particle at once with larger brush sizes. With my handle_clicks system it wasn't too hard to implement this, but it is necessary to capture some keyboard inputs to change the brush size.

My MVP doesn't really include designing a UI so for changing the brush size I am just going to cature up and down arrow inputs. Much like mouse inputs Bevy makes it easy to capture keyboard inputs.

The brush size itself uses Bevy's resource system, which is also used for mouse and keyboard events. Essentially it allows for something that is going to be needed by lots of systems to be stored and accessed safely.

Firstly I defined a BrushSize enum with the desired range of sizes:

Then inside setup I create an instance of the resource with a starting brush size.

The next step is to spawn particles in all valid locations according to the brush size. There are a number of ways this could be done but I wanted to practice using Rust's iterators.

The function get_brush_locations is given the coordinates of the center of the brush location (mouse click location) and the desired brush size. The brush size is pattern matched to give the radius of the brush from the centre called delta. This delta is then applied to the x and y values as well as the itertools cartesian_product iterator which gives a nice way of iterating over two value ranges.

The resulting iterator is then returned.

// in brush.rs

Now handle_click is modified to use this. Instead of trying to spawn a particle at one location, get_brush_locations returns an iterator over all the coordinates within the brush and each of these is then checked to be in the fun zone and then placed.

// Still very simplified

The Gravity of the Situation

Something missing from this particle simulation at the moment is a bit of, well, simulating. The most basic simulation here is gravity, which I already promised the sand when I place it.

Gravity is another system and will demonstrate how Bevy allows you to query a desired set of components according to what you want to operate on.

Before any of that though there is another part of this system that I have been hiding until now which is pretty important for the performance of the game.

Remembering a Universe

To simulate gravity at its simplest level, as in this game, is of course simple.

Anything below me? No? Down I go.

Considering a single gravity smitten particle. To do the above could be done by checking the location of every other particle in the fun zone and checking if it is below ones-self. If after checking all of them there is no-one underneath then chucks away. What would be a lot faster is only checking the spot directly below, and nothing else.

To do this though requires some sort of tracking system for the whole universe.

Okay not the whole actual universe but certainly the whole of the universe centralised within the fun zone.

By keeping track of an array of Element and then turning coordinates into flattened indices it is easy to keep track of the current make up of the universe at relatively low cost. With any luck Rust will spot that the enum could be replaced with something as small as a u8 and smartly pack it into less memory, but our universe isn't too big so it should be okay regardless.

The Universe is a struct (not our universe). It contains elements an array of fixed size with Element at every point. At the start the universe is empty (okay this seems to be true for our universe as well) and will slowly be filled up as time goes on.

// create fixed size universe

This is then rammed into a resource like the brush and the universe is told an element has appeared when the player clicks. Bosh.

Falling For You

Now on to the gravity itself which should be very easy now we have the universe pinned down and bottled up.

Having said that I do expand slightly on the simple definition of gravity earlier, just to bring a little bit more pizazz. If there is something under a particle, but there is nothing below to the side, I want the particle to slide.

This is very basic sliding behaviour but it looks pretty cool anyway and lets you make big pyramids instead of large monolithic towers. A refinement later could be limiting sliding to particles with a Slide component.

The gravity system uses Bevy's query system. It gathers up all the components that match the query and lets you act on them, be it read or write. It also allows filters with the With trait so we can enact gravity on the transforms of particles that expect it.

From here its a case of checking below, to the left and write and placing the sand accordingly. Also letting the universe know along the way.

To be continued

With the design of Bevy's ECS and the way I have been using it it should be pretty simple to return from time to time to try and implement a new feature and bring this little demo closer to the games I used to play. It could also serve as a playground for me to try out other cool ideas, such as wave function collapse for plant generation.

Currently I am working on getting the game working in web-assembly, hopefully it shouldn't be too hard as Bevy has a feature set allowing it to compile to wasm so fingers crossed.

Until then the MVP I defined has been reached so it's time to move on to some other new project...